58. Venecijansko bijenale i deset najboljih paviljona prema mišljenju Casey Lesser-a. Portal Artsy.

Installation view of Laure Prouvost, “Deep See Blue Surrounding You/Vois Ce Bleu Profond Te Fondre,” for the France Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, 2019. Courtesy of Institut français. The best way to take the pulse of contemporary art worldwide may be by visiting the Venice Biennale’s national pavilions. Representing a “plurality of voices,” as Biennale president Paolo Baratta said at a press conference on Wednesday, these spaces are fertile ground for artists to address the current state of their countries and the world at large. And at the 58th Venice Biennale this year, alongside Ralph Rugoff’s exhibition, “May You Live in Interesting Times,” artists are sending cogent messages to their governments, encouraging community, and telling fresh stories that build empathy. Here, we share the 10 most dynamic and captivating pavilions in the Arsenale and Giardini.

Australia, Angelica Mesiti, “Assembly”, Curated by Juliana Engberg, Giardini

Installation view of Angelica Mesiti, “Assembly,” for the Australia Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, 2019. Photo © Josh Raymond. Courtesy of the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Australia and Galerie Allen, Paris. Angelica Mesiti wanted to turn the Australian pavilion into a site of democracy and community. Her three-channel film plays around a red-carpeted, mini amphitheater, where visitors can sit side by side, and take in the captivating work. The film uses music to address the flailing state of democracies globally—particularly, the cacophony of conflicting voices and viewpoints. Filmed in the plush senate chambers in Italy and Australia, the piece encourages listening and harmony, through becoming attuned to the ways that we communicate.

The starting point of the piece is a device used by stenographers known as the Michela machine. Mesiti translated a poem by David Malouf using the device, then had the resulting coded language turned into music by composer Max Lyandvert. We see performers in the film play this piece, including a crew of musicians vigorously beating illuminated bass drums. An earnest female protagonist in the film is seen making deliberate hand signals. The gestures signify concepts like disapproval, silence, and opposition, and were used in a 2017 Nuit debout protest in Paris against the controversial labor legislation El Khomri.

Poland, Roman Stańczak, “Flight”, Curated by Łukasz Mojsak and Łukasz Ronduda, Giardini

Installation view of Roman Stańczak, “Flight,” for the Poland Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, 2019. Photo by Zachęta. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art/Weronika Wysocka. For the Biennale, Roman Stańczak

cut an airplane in half and reconstructed it inside-out. Sitting idly in its hangar—a.k.a. the Polish pavilion—the mid-size aircraft is an incredible jumble of wires, straps, windows, and metal plates, yet it still vaguely resembles the original thing. The artist deconstructs objects in order to create something new, as a way of finding meaning and as a spiritual exercise to come to terms with death. He considers it a means of seeking out hope—teaching others new ways of seeing.

Roman Stańczak, “Flight”

The piece speaks specifically to conflicts in Polish society, particularly its capitalist regime. By taking apart a private plane—a symbol of the ultra wealthy—the artist makes a cutting critique of Poland’s capitalist regime. But on a universal level, it speaks to global instances of economic and social inequality. Ultimately, Stańczak’s wildly complex feat gives us a reason to rethink the spaces we inhabit, and the realities we abide by.

United States, Martin Puryear, “Liberty/Libertá”, Curated by Brooke Kamin Rapaport, Giardini

Installation view of Martin Puryear, “Liberty/Libertá,” for the United States Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, 2019. Photo by Zachęta. Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of Madison Square Park Conservancy. Before you even set foot in the American pavilion, it’s clear that Martin Puryear is making a statement. The pavilion in the Giardini was built in 1930 and modeled after Thomas Jefferson’s Neoclassical estate Monticello. But you won’t be able to tell this year, because Puryear closed in its courtyard and obscured the façade with a looming wooden screen, Swallowed Sun (Monstrance and Volute) (2019). The slaveholding Jefferson’s home was an active plantation. “The pavilion becomes deeply symbolic, then, for this exhibition, for the artist who exposes its inherent contradictions,” explained curator Brooke Kamin Rapaport at a press conference. Martin Puryear, “Liberty/Libertá”

The title Swallowed Sun (Monstrance and Volute) “refers to the darkness of a solar eclipse or the despair of a conceptual blackout when values are in jeopardy,” Rapaport added. The work’s perforations allow the visitor to “peer through the barrier and into the historical past.” The artist’s clear-eyed vision extends into the pavilion where fresh works mingle with his signature forms, including the Phrygian cap. A highlight is a new sculpture, A Column for Sally Hemings (2019), in the rotunda: a cast-iron shackle driven into a pristine white column that is in tribute to the titualar woman, an African-American slave who worked for Jefferson and had children with him. “Martin Puryear is moved with urgency to communicate society’s deep-seated conflicts and the stunning march of time,” Rapaport noted.

Brazil, Bárbara Wagner & Benjamin de Burca,“Swinguerra”, Curated by Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro, Giardini

Installation view of Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca, “Swinguerra,” for the Brazil Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, 2019. Photo by Riccardo Tosetto. Courtesy of Fundação Bienal de São Paulo.Bárbara Wagner & Benjamin de Burca

’s two-screen film is a cinematic, documentary-esque piece that captures the little-known dance phenomenon of the Brazilian music genre swingueira. In the Brazilian city of Recife, groups of young, black Brazilians, many of whom are nonbinary, form groups of as many as 50 to 100 dancers. They rehearse choreography several times each week, all year, to enter into competitions. The film, Swinguerra, is titled to include the Portuguese word for war, guerra, which reflects the conflicts at the heart of those competitions and the dancers’ lives. The piece shows their incredible dedication, athleticism, and synchronicity as they rehearse and stage elaborate performances. Their passion and energy is infectious, but it’s also an expression of the oppression they experience. Wagner and de Burca have been working on the piece since 2015, in collaboration with three dance groups.

The artists gave their subjects agency in determining everything from choreography to costumes to the sequence of shots and film locations. Curator Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro noted that this approach is in fresh contrast to the anthropological tact that artists have long used to address marginalized peoples. “That collaborative process seems original, interesting, and appropriate for the times that we’re in,” he said.

Wagner explained that the dancers are part of a large black population in Recife that is “completely invisible in the art world.” She added: “For us, we don’t need to talk about power, resistance, race, and gender in the work, we don’t need much more than just allowing the collaboration to happen. It’s a simple gesture, but it’s everything.”

Ghana, Felicia Abban, John Akomfrah, El Anatsui, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Ibrahim Mahama, and Selasi Awusi Sosu,“Ghana Freedom”, Curated by Nana Oforiatta Ayim, Arsenale

Installation view of the Ghana Pavilion, “Ghana Freedom,” featuring Felicia Abban, Untitled (Portraits and Self-Portraits), c. 1960–70s, at the 58th Venice Biennale, 2019. Photo by David Levene. Courtesy of the artist. Ghana’s first-ever national pavilion at the Venice Biennale is a triumphant tribute to the country’s deep cultural roots, through six of its beloved artists. Ghana gained independence in 1957 under President Kwame Nkrumah, a great supporter of the arts, explained curator Nana Oforiatta Ayim at the press preview. The title comes from a song by E.T. Mensah, an artist Nkrumah supported, “which speaks of the freedom Ghana gained at the time,” Ayim said, “and this exhibition explores how that freedom has manifested itself and how it’s evolved in different forms and patterns over time.”

Ghana Pavilion, “Ghana Freedom”

France, Laure Prouvost, “Deep See Blue Surrounding You/Vois Ce Bleu Profond Te Fondre”, Curated by Martha Kirszenbaum, Giardini

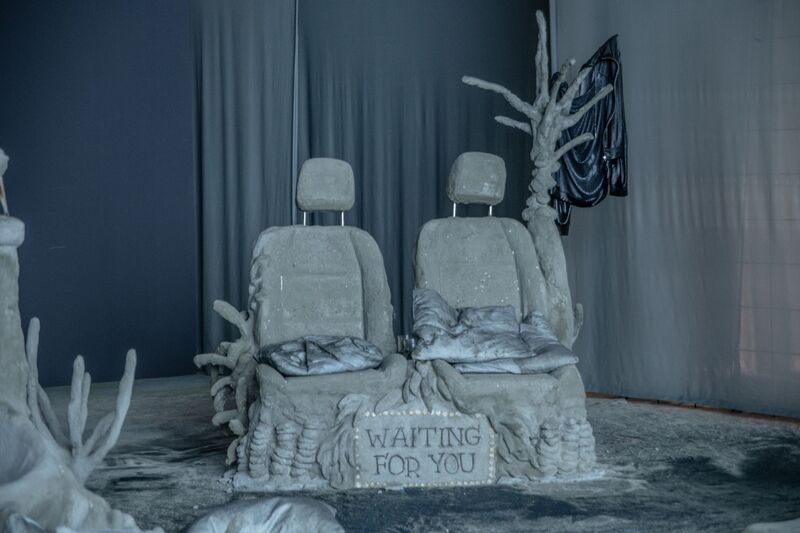

Installation view of Laure Prouvost, “Deep See Blue Surrounding You/Vois Ce Bleu Profond Te Fondre,” for the France Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, 2019. Courtesy of Institut français. The Turner Prize–winning Laure Prouvost

takes us on a euphoric journey to Venice in her French pavilion. Walk in from a back door, and you’re met with a rubble-filled basement, allegedly the start of the artists’ plans to dig a hole between the French and British pavilions. Upstairs, a bright-white room with a clear, seafoam-blue floor is embedded with strange still-lifes made from cell phones, branches, eggshells, glass sculptures of sea creatures, and even real doves. Go through soft gray curtains to find the main event—an engrossing, stream-of-consciousness film. The piece unfurls the fictional expedition of an eclectic crew of varying ages and backgrounds as they travel from Paris to Venice.

Prouvost’s script is a veritable artwork in itself, toying with language and translation as it swiftly jumps between English and French, with dashes of Italian, Arabic, and Dutch. She peppers in humorous phrases, like “Most onions will be electric. You’ll be the WiFi,” and sends the protagonists into tangents that appear to be, at times, symbolic or nonsensical. Striking vignettes include a lush fig kissing a bare breast; a young man jumping off the roof of the pavilion and becoming a seagull; and a pink octopus. Prouvost is drawn to the mollusk for the way it carries brain cells in its tentacles. She’s also worked in her signature motif, the boob, in the form of Venetian glass. Though utterly confounding at times, the film is undeniably joyous, visually stunning, and aurally soothing—a glorious reminder of the transformative power of art.

India, Nandalal Bose, MF Husain, Atul Dodiya, Jitish Kallat, Ashim Purkayastha, Shakuntala Kulkarni, Rummana Hussain, and GR Iranna, “Our Time for a Future Caring”, Curated by Roobina Karode, Arsenale

Installation view of the India Pavilion, “Our Time for a Future Caring,” featuring GR Iranna, Naavu (We Together), 2012, at the 58th Venice Biennale, 2019. Courtesy of the artist. In its second-ever showing at the Biennale, India is honoring the 150th anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi’s birth. Rather than showing literal representations of the celebrated leader and activist, however, curator Roobina Karode, director and chief curator at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, chose eight artists who channel Gandhi’s timeless influence. Sculptures, installations, painting, and video evoke peaceful protest, passive resistance, and respect for the environment.

India Pavilion, “Our Time for a Future Caring”

The crown jewel of the pavilion is an installation, Covering Letter (2012), by the Mumbai-based artis

Switzerland, Pauline Boudry & Renate Lorenz, “Moving Backwards”, Curated by Charlotte Laubard, Giardini

Installation view of Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz, “Moving Backwards,” for the Switzerland Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, 2019. Photo by Pro Helvetia/KEYSTONE/ Gaëtan Bally. Courtesy of the artists. Artist duo Pauline Boudry & Renate Lorenz wrote a bold letter simultaneously welcoming visitors to their Swiss pavilion and rejecting their government. The first line reads: “We do not feel represented by our governments and do not agree with decisions taken in our name.” They go on to express their concern over European nations building walls and refusing refugees; rampant hate speech; and a decline in the use of gender-neutral language and polyamory. They propose a recipe for the contemporary state of the world: “Let’s collectively move backwards.”

This statement of resistance comes to life in their pavilion, tapping into contemporary dance and queer underground culture. In a video installation, five dancers from distinct backgrounds follow jaunty choreography and hip-hop moves, progressively becoming more expressive with the beat of the music. Some cuts feature the dancers moving in reverse, to the point where the viewer is left wondering which way is forward—a poignant question for the present moment. By the end, some audience members might have a hard time not dancing along. And that spirit continues in the next room, an “abstract club” that you enter from behind the bar. There, the artists offer up newspapers they created, filled with letters from fellow artists, scholars, activists, and philosophers proposing their own thoughts on moving backwards.

Philippines, Mark Justiniani, “Island Weather”, Curated by Tessa Maria Guazon, Arsenale

Installation view of Mark Justiniani, “Island Weather,” for the Philippines Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, 2019. Photo by Italo Rondinella. Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia. Walk into the Philippine pavilion, remove your shoes, and climb onto the artworks—sleek islands filled with mirrors that create an infinity effect. Stare down, and you’ll find an endless abyss, punctuated by objects that are specific to the archipelago nation, ranging from plants and spices to a stack of documents. Artist Mark Justiniani reflects on the thousands of islands that make up the Philippines, contemplating the land masses as they relate to the nation’s colonial history, the environment, and social issues. One of the islands, with a ladder leading to a perch on top, is meant to reference the formation of a typhoon or a cyclone. It’s also a nod to the fact that first observatory in the Far East was established in the Philippines.

“We call it Island Weather because the weather is not just atmospheric weather, it’s about the state of the world, how fickle situations can be, and how vulnerable we are,” said curator Tessa Maria Guazon. By allowing viewers to experience the work by walking on it, Justiniani tapped into “a kind of seeing,” Guazon added, that emphasizes “how deceptive appearances are.”

Kosovo, Alban Muja,“Family Album”, Curated by Vincent Honoré, Arsenale

Installation view of Alban Muja, “Family Album,” for the Kosovo Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, 2019. Photo by Italo Rondinella. Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia. During the Kosovo War in 1998–99, photographs of child refugees became the face of the conflict as their likenesses were printed in newspapers worldwide. Twenty years later, artist Alban Muja —who was himself a child refugee during that war—tracked down the children featured in some of those famed images and captured their stories. In the Kosovo pavilion, he shows three vivid, emotional videos that foreground these subjects, now adults. They recall the circumstances of their photographs and reflect on the influence the images had on the media—and on the mainstream understanding of the war.

One young woman, Besa, was pictured in a photo as her mother breastfed her. Based on memories from her parents, she describes how her mother protected her, once even warming her in an oven when she feared her baby had died from the cold. The 21-year-old Agim tells the story of his photo, taken when he was 16 months old and was passed over a barbed-wire fence. The featured videos are not only moving accounts of a former crisis, they also resonate with the contemporary narratives of refugees worldwide. “Today, when I see news about refugees around the world, I get goosebumps,” Agim recalled, “because I know that in 1999, my family also experienced what today’s refugees around the world are going through.”